Knowledge Economy and Tertiary Education

In this first week of the unit, we will read and discuss some key documents about two related concepts, human capital and the knowledge economy. The concepts have been informing policy and discourse about tertiary education for decades. One of the main policy players is the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a club of sorts for wealthy, industrialized countries. Member countries include all of the countries of the European Union, Australia & New Zealand, Japan, Canada and the US.

The OECD conducts research and publishes reports on key areas of social and economic policy, including education. It is worthwhile to read OECD documents as their conclusions often influence policy makers and government officials. The articles by Robinson and Brown provide counter-arguments to the dominant discourse about human capital, education and the knowledge economy

Education Policy Analysis, OCED, 2001 and 2002

Learning Objectives: OECD articles

1. Human capital: What is it? How is it different from other forms of capital? Why is it relevant to individuals and nations? How is it created?

2. Knowledge economy: What is it? How is it different from other types of economy? What role does education play in this type of economy?

3. Role of tertiary education: What is tertiary education? What is its role in human capital formation and the knowledge economy?

P. Brown, European Education Research Journal, Vol 2:1, 2003,p141-179

Learning objectives: Brown

1. Opportunity trap: What is it? Do you agree that it exists? Can you think of some counter arguments?

2. Discuss the relationship between education, opportunity, social mobility and social justice. When, and for whom, does Brown argue that education promotes social mobility? When, and for whom, does it not?

3. Discuss the screening/selection functions of education; discuss credentialism and “diploma disease.”

4. How do you think would Brown account for the fact that most industrialized countries suffer labor shortages in areas that require university qualifications (e.g., teaching, nursing and medicine, accounting, engineering, maths & sciences, etc.)

P. Robinson, The Tyranny of League Tables, 1999

Learning objectives: Robinson

1. What are some common myths about the relationship between economic performance and educational achievement and attainment?

2. What does the data say about the relationship?

Being someone with a bit of background in classical political economy, I grimaced a bit when I saw "human capital" in the first week's readings. In political economy, capital is what is owned by capitalists, from which they receive a return from. It is machinery part of the factors of production, distinct from natural resources and labour. The attempt to combine the productivity of labour with capital ownership set off all sorts of noisy warning bells in my head, not least inspired by this quote from Milton Friedman.

"The counterpart for education would be to 'buy' a share in an individual's earning prospects: to advance him the funds needed to finance his training on condition that he agree to pay the lender a specified fraction of his future earnings. In this way, a lender would get back more than his initial investment from relatively successful individuals, which would compensate for the failure to recoup his original investment from the unsuccessful. There seems no legal obstacle to private contracts of this kind, even though they are economically equivalent to the purchase of a share in an individual's earning capacity and thus to partial slavery."

Wait until training offers from employers include contracts like that...

Concerning "human capital", as mentioned the term seems to have some definitional and practical issues.

In classic political economy, the primary factors of production were land (i.e., all natural resources), labour, and capital. Capital represents durable goods that are used in production of goods or services. It contrasts with the accounting definition of "capital" which refers to stocks, shares, currency etc representing the perceived exchange value of such durable goods. Marx, rather delightfully, described the latter as "fictitious capital"!

There is a belief that political economy did not include "intangibles", such as organisation efficiencies, individual entrepreneurship, consumer goodwill, or skills and knowledge. This isn't quite true, as there was recognition for example, of "labour power", the variable capacity of each additional unit to the productive process, or likewise the productivity of machinery, or the from various grades of land (from Ricardo).

Nevertheless the perception of this alleged lack has led to a proliferation of capital theory especially since the 1960s. Today there is volumes of material describing "human capital" (i.e., skills and knowledges), "social capital" (networks of trust), "intellectual capital" (intellectual property), "cultural capital" (particular aesthetic tastes) and so forth. Whilst I appreciate the increasing definitional accuracy for secondary factors of production, I don't think that most of these are a category in their own right, and I am very doubtful that some constitute a type of "capital", except perhaps in the case of social capital which represents an investment in positive externalities [1].

As per the reading in the course material, the OECD defines human capital as "The knowledge, skills, competencies[,] and attributes embodied in individuals that facilitate the creation of personal, social[,] and economic well-being". Whilst one could engage in a metaphor of investing in knowledge and skills (i.e., education and training) to produce utility ("well being") and that these knowledge and skills may depreciatate, and could be subject to "capital flight" as 'owners' of the human capital depart for places that offer better wages. If the metaphor is followed further perhaps "attributes" could be considered something closer to "human land" instead, although it should be pointed out that neoclassical economics tends to, incorrectly in my view, conflate land and capital. Indeed arguably, the discussion of "human capital" does look like an attempt to convert labour, as a factor production, into capital as well. Apparently everything is capital now!

In all of this, it must be kept in mind that political economy is primarily concerned with the moral claims to ownership. Neoclassical economics is more concerned with positive rather than normative economics and as a result often overlooks such issues (it does have other advantages however, such as marginal analysis).

From the perspective of the OECD "[a]bout 40% of individual variation in earnings through IALS [International Adult Literacy Survey] measures such as educational qualifications, literacy[,] and work experience, combined with background factors of gender, language[,] and parents' education levels. With sixty percent unaccouonted for, the OECD report proposes a wider conception of human capital to include self-management characteristics such as the desire for learning, wisdom in the application of skills, and trustworthiness, motivation, & etc. The wider perspective also contributes to positive externalities (such as reduced smoking, criminal involvement, participation in community groups being correlated with additional full-time education).

Whilst a review of other readings will put the claim of "human capital" as being directly correlated to economic growth and social capital under greater scrutiny, from the outset it seems that the term "human capital" is not really the right one, as it does not share the definitional characteristics of "capital" in an economic sense, and nore does it share the ownership relations. It would be better to call investment in labour what it actually is - and remove an potential ambiguity that the owner of skills and knowledges (and attributes and motivations), is the worker where they are ontologically located.

Endnotes

[1] There is an interesting contrary point of view by Andy Blunden just released just yesterday afternoon entitled "Social Solidarity versus Social Capital" available at: http://www.academia.edu/3746209/Social_Solidarity_versus_Social_Capital_

Comment from: Sarah W.

In the nursing profession, I am aware that there is research that participation in postgraduate studies has links with improved patient outcomes. So I think the value of higher degrees is worth more when put into this context. It is a nurse educators dream that a ‘Masters in Nursing’ be common practice, especially with clinical staff. While I completely believe that participation in higher degrees leads to improved patient outcomes and this is the best excuse to participate in postgraduate studies, I have never paused to reflect on who conducted the research and what their potential motives where to increase the nursing knowledge economy.

“..number of middle-class occupations has increased, although UK data show that this remains far below that required to meet current demands.” (Brown, 2003, p.150).

“Problem of too many contestants chasing too few prized jobs.” (Brown, 2003, p.152).

In the immediate nursing economic environment, we face the issue of having surplus numbers within the knowledge economy- BUT, give it 5 years, and we are in serious trouble (over 100,000 short across Aus). Adding Australian data to the above statements may prove interesting.

I am not sure if it is my misinterpretation of this topic or not- but the first 2 readings feel very mechanical and presumptuous about the impact of a qualification on the ability of someone to obtain a ‘better’ job that will improve their economic status. I felt like they were trying to stereotype a certain individual as being ideal contributors to increasing the knowledge economy. I would love to hear what everyone else is thinking, because I think I may have missed a very important element to this!

My Response

The article by Brown explicitly takes issue with the claims from the OCED of investment in education providing "opportunity, prosperity[,] and justice", specifically arguing that "social inequalities in the competition for a livelihood and an intensification of 'positional' conflict". Brown argues that everyone must engage in this rush for positional advantage in order to maintain their current standard of living. We "have to run faster, for longer, just to stand still". This is "the opportunity trap". The argument elaborates both prior symptoms of the "diploma disease" and uses the core insights of the sociology of education as elucidated by Durkheim (i.e., the socialisation role, and the selection role).

Brown elaborates a positional consensus and conflict theory that starts on the former with the observation that increasingly complex societies will require professional and technical workers. These new professions will "generate new opportunities for jobs that offer excitement, creative fulfillment, and personal development. Work is the new consumption." From a conflict perspective however, "The expansion of higher education is not believed to reflect changes in the demand for high-skilled workers, but credential inflation ... The idea of credential inflation is similar to monetary inflation".

The theory of the opportunity trap is "rooted in the relationship between capitalism and democracy... aspirational working-class families have high hopes of what the knowledge economy has to offer.. [but] the labour market cannot keep pace with social expectations of work, rewards, and status", reflected in a "trend for increased demand for technical and professional workers and a more intensive struggle for competitive advantage in education and the labour market". Increased wages for such workers does not come from "the human capital idea that learning pays" but rather from "a decline in the earning power of non-university graduates", which conforms with the expectations of positional conflict theory.

Brown concludes that the twenty-first century is "Hobbesian", which one presumes is meant a "war of all against all" (bellum omnium contra omnes) in the labour market. "Opportunity, rather than being the glue that bonds the individual to society, has become the focus for intense social conflict" as we have "entered a period of 'educational stagflation', where inflationary pressures on credentials continues, and at the same time the job market cannot create enough jobs that many expect".

There is much in Brown that is agreeable in terms of taking a conflict position, but perhaps a simpler explanation is readily available rather than apparently placing a great deal of the blame for such a situation on aspirational and educated members of the working class. Rather, what is being witnessed is an intensification of "old-fashioned" class war between the owners of land and capital against working people. Such an analysis takes issue with Brown's claim that: "If in the future everyone had a PhD or the like, then these advanced degrees would be worth no more than a job in a fast food restaurant." If we engage in such a though experiment it would be quickly realised that a society where everyone is a post-doctoral (or equivalent) graduate would not only be a pleasant society to be in, but it would also have enormous increases in overall productivity through the implementation of (a) new technologies that produce more for less and consumer goods that save time and energy, (b) new social organisation and legal norms with greater moral grounding and (c) aesthetic products that provide greater inspiration.

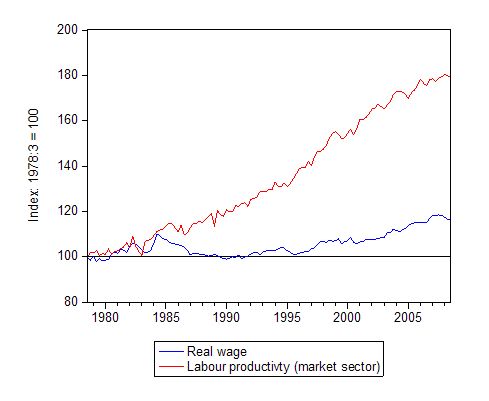

Now, to an extent such possibilities do exist and too a degree, at least in category (a) and possibly (c) as a commercial product, they have been introduced. This can be evidenced by the enormous improvements in productivity over the last forty years. However where there is a serious lack is the improvements in (b), indeed, there is strong evidence of a decline. This can be illustrated by a matter as simple as comparing increases in real wages from the 1970s to now, educational qualifications, and overall productivity for the same period. The following graph, covering two of these three variables, for the United States, should be illustrative enough.

Simon L asked:

One of the issues that Brown (2003) raises is education becoming more acquisitive than inquisitive.

While I really like a lot of what Brown says and agree with many of the ideas, the world I'm in seems more complex than is described by him. One example of this is the changing focus he suggests from acquiring (education, credentials) rather than inquiring.

I'm interested in others' thoughts on this. Are your students more acquisitive in their approach than they might be, or used to be? Or for yourself, is your enrolment in this course for the purpose of acquiring the qualification or are you driven 'by an interest in knowledge and learning for its own sake'?

What I see is that many of my students (in the TAFE sector) are driven by either or both motivations. Sometimes if they enrol for acquisitive motivations they actually use their inquisitive motivations during the duration and this is what gets them to completion.

This point kind of ties in with the league tables article (Robinson 1999) because there's a lot of research gone into the differences between mastery goals (I want to be good at this) and performance goals (I want to get a good mark), with some of it showing that those driven by mastery goals persist more and work harder. There seems to be a connection there; if we're more acquisitively motivated predominantly, are we more likely to be driven by performance (not mastery) goals? Maybe someone has some thoughts on the impact of NAPLAN testing...?

Do you see or think that the global economy labour market has made people more acquisitive in their approach to education?

My response

The distinction between acquisitive and inquisitive course selection is very much reminiscent of the continuum of motivations of learning from the external to the intrinsic [1]. Given that everything about a learning experience is to some degree socially located, there is always some external motivating influence. To Sheldon, older learners seemed to take on more self-concordant goals, i.e., they were more intrinsic, more inquisitive, as their external and acquisitive desires were less.

A similar comparison and elaboration can be made between the difference between mastery and performance goals and the difference between summative and formative assessment methods [2], where formative assessment concur with mastery goals and performance with summative assessment methods. Formative assessment that indicates mastery suggests an intrinsic satisfaction, where as summative assessment that provides a perfomance goals that are for external application.

The two dichotomies however seem a little simplistic, as they overlook the possibility of not just a continuum, but rather a a multiplicity of simultaneous motivations that can occur in an individual educational decision. A person may, for example, be both sincerely interested in organisational theory and practise as well as motivated by the possibility of acquiring a stiff piece of carboard which allows them to use the letters "MBA" as a post-nominal. Likewise, a summative assessment that provides external validation may also provide formative and internal satisfaction.

The question is raised obviously If these dichotomies are not a continuum, then what are they? Are they completely independent metrics or they dependencies? An initial consideration leans towards the latter, based merely on the observation of those who seem unduly influenced by external influence, validation, and acquisition. One only has to encounter such individuals who have studied in a field that they do not care about, for rewards that provide but material satisfaction without internal joy, to see the dissonance that results in taking up acquisitive goals without an intrinsic justification.

References

[1] Sheldon, K. M. (2009). Changes in goal-striving across the life span: Do people learn to select more self-concordant goals as they age?. In M. C. Smith (Ed.), Handbook of research on adult learning and development (pp. 553–569). New York: Routledge.

[2] Ramsden P. (1992). Assessing for understanding. Chapter 10. In P. Ramsden, "Learning to teach in higher education", London & New York: Routledge.